When two homeless men, Daniel Aldape and David Dunn, were bludgeoned to death on the street in downtown Las Vegas in separate incidents in January and February 2017, Captain Andrew Walsh of the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, knew he needed to act fast and use all available department resources: He was dealing with a potential serial killer.

Although there were no weapons left behind at the crime scenes, no witnesses to the killings and no surveillance video, Walsh’s experience and intuition—he’s been in law enforcement since 1992—told him the murders were linked and the killer would soon return.

Walsh needed a bold idea to capture the murderer haunting Las Vegas’s streets—a city visited annually by over 40 million people with a homeless population of over 6,000 people—before the criminal slipped away. His idea: to use a mannequin, disguised as a homeless person sleeping, as part of a sting operation to lure the killer back to the same spot.

After three weeks, Walsh’s outrageous plan worked. On February 22, 2017, Shane Schindler was caught on video attacking the dummy with a hammer. He pleaded guilty to attempted murder and on August 24, 2017 was sentenced to eight to 20 years in prison.

Walsh, who is now a deputy chief, spoke to A&E True Crime about developing the plan to use the mannequin, how the unusual sting went down and how the family of one of the victims inspired him to continue the pursuit.

How did you first learn about the killer?

The first murder victim was Daniel Aldape. He was found bludgeoned with a severe head injury…while he was sleeping. His skull was crushed.

It’s not uncommon for Las Vegas to have homeless crime. Sometimes it does lead to murder. One of our working theories was maybe [the killer] had an argument or dispute with someone from that community. Then almost a month to the day, right across the street, a second person was found killed. We know something was happening.

When you heard about the second murder, did you suspect a serial killer?

My initial reaction was that both killings were connected. Clearly they were related by the fact of the geography and how close they were together and they were both homeless. They were both sleeping in open areas by themselves outside in January. That’s the last time they were seen alive until people went to check on them in the morning. That’s when they were both discovered to have been killed.

I’ve seen enough cases and have enough experience to know two murders that happen across the street from each other in an area couldn’t be a coincidence.

How did you get the idea to use the mannequin?

The idea of using a dummy just popped into my head. In these cases we didn’t have any evidence. We had to use good old-fashioned instinct and intuition. We knew we had to try something different. My role was making sure we could do something with the patrol resources that was proactive, as we had an obligation to utilize the power of the police department to hunt down the killers.

When I thought about the dummy idea I didn’t [originally] tell anybody. I reached out to the captain in charge of our search-and-rescue section and asked him if they still used life-sized sea and rescue CPR mannequins for training. He said, ‘Yep, we have a couple.’ I asked him if we could borrow one. I told him what I was going to do and he chuckled and said, ‘Yeah, that’s a good idea.’ We ran with it from there.

Were you inspired by other any other unusual suspect-catching techniques used in police departments around the country?

No, I’ve never heard of anything like using a decoy to lure a murderer. That was part of what made people uncomfortable. Our police department studies best practices from around the country and there was nothing along these lines. The everyday thinking of decoy operations is to use them in either undercover situations, narcotics stings or vice operations. But for murders? Never.

How did officers react to implementing this idea?

Folks that worked for me thought I was out of my mind, but they followed the plan. Word got out around the department, and people didn’t hesitate to come up to me and tell me I was crazy and it wouldn’t work. The reality was I couldn’t afford not to try everything. As crazy as the idea sounded—and it didn’t sound too crazy to me—I didn’t sway from [it].

In the end, the officers ran with it. The detectives were smart about how they put the dummy out. They did it at the right time and it became routine after a while, because the homeless population sticks to their routine. They picked good times to go in, when they knew they wouldn’t be seen.

The idea was just a vision on my end, but they were motivated to try and find the person responsible. It was really good work on their part.

How was the plan put into operation?

I told my workforce we were going to put the dummy out and do surveillance. We had cameras installed in that intersection and we put human surveillance out.

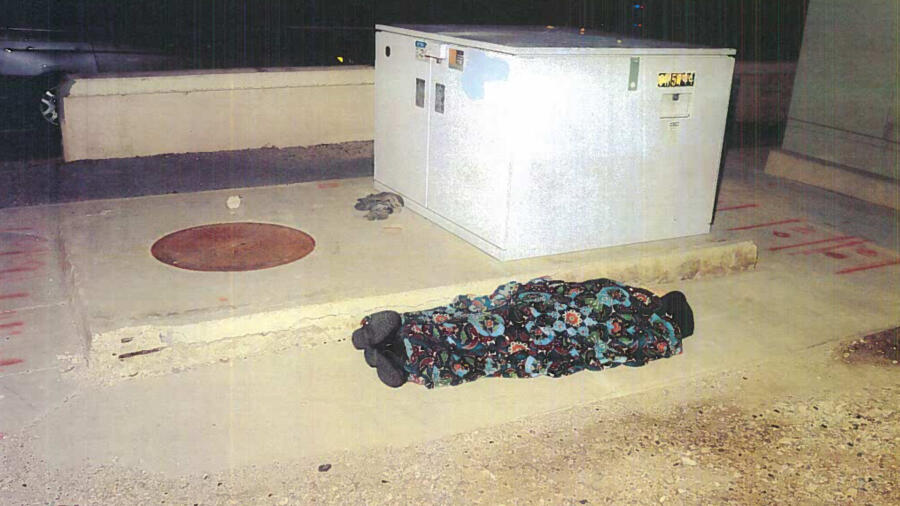

[The officers] perfected a plan and had a schedule [of when to put out the decoy] and took it upon themselves to make [it] look as human as possible, dressing it up.

A sergeant brought in some boots and one of his wife’s blankets. They got a knit hat. [They] watched how the homeless guys set up their sleeping areas at night—they set it up to make it look like it was a person sleeping.

How did the officers adjust to working with the mannequin?

We named the mannequin “Charlie McCarthy” after puppet master Edgar Bergen’s [dummy]. He used to appear a lot on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and my parents used to let me stay up and watch.

Charlie [the mannequin] would come from area command every day. We’d drive Charlie around and he just became one of the team. The detectives would park, walk Charlie over and set him up as if he were sleeping. Then the surveillance would begin. Once daylight broke, the detectives would scoop him up and put [him] in the car.

Did the victims’ families know about the plan?

They were grateful. I never met Daniel Aldape, but I feel like I got to know a lot about him through the stories from his family. He had a family that absolutely loved him and he loved—he just choose to live outside and be homeless. That’s his right and his choice.

When he was killed, they thought we wouldn’t do anything about it because, in their words, he was ‘just a homeless guy.’ They didn’t think we would care. We showed them that we did.

What was your reaction after Shane Schindler tried to bludgeon the mannequin and was arrested?

The sergeant called me at 3:30 a.m. and he was very excited. He kept talking about ‘murders,’ but I couldn’t understand what he saying. Then in plain English he said ‘The dummy got attacked’.’ It became clear. I woke my wife up and told her the mannequin got attacked. It didn’t seem possible!

Then the officer quickly transitioned to how we move forward. In planning the dummy operation, the unknown was always: What happens if the mannequin gets attacked? The District Attorney’s office had to come up with charges and make them stick. We knew we had the right guy but didn’t know if we could ever charge him with murder.

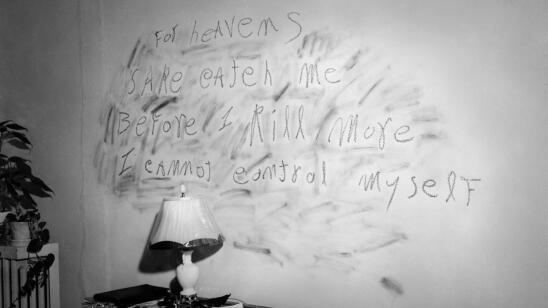

The District Attorney took it upon themselves to make sure he didn’t get away. In the video, it’s pretty clear Shane Schindler would’ve killed another human being that night.

What advice would you give other police departments about trying unusual ideas to catch suspects?

Leadership has to be the ones driving the message or tactic. Commanders need to accept criticism or failure if an idea doesn’t pan out. But they have to try new things and not worry about what people think. Our biggest worry should be about saving lives.

Police departments can be proactive. I still can’t believe we solved these murders. To have been a part of it is humbling.

Related Features:

Live PD’s Sgt. ‘Sticks’ Larkin’s Top 5 Most Unusual Arrests

Dan Abrams on the Most Surprising Things He’s Learned About Cops on Live PD

Good Cop, Bad Cop: A Retired Detective on the Best and Worst Cops He Knows